Holography Course Illuminates Undergrad Minds at U of T

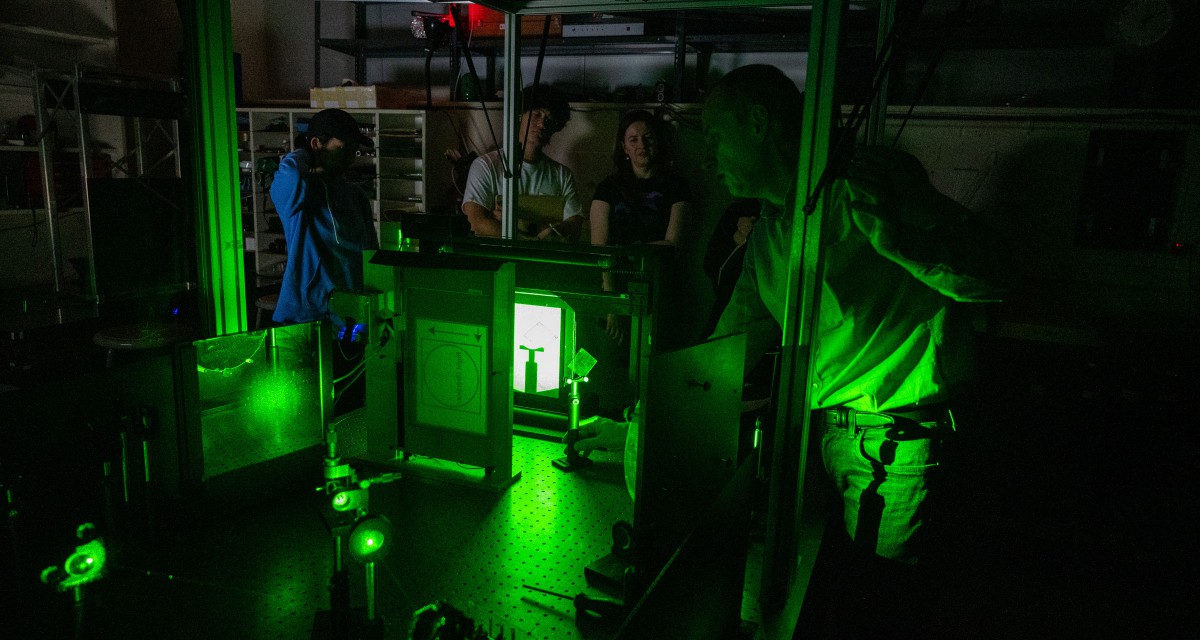

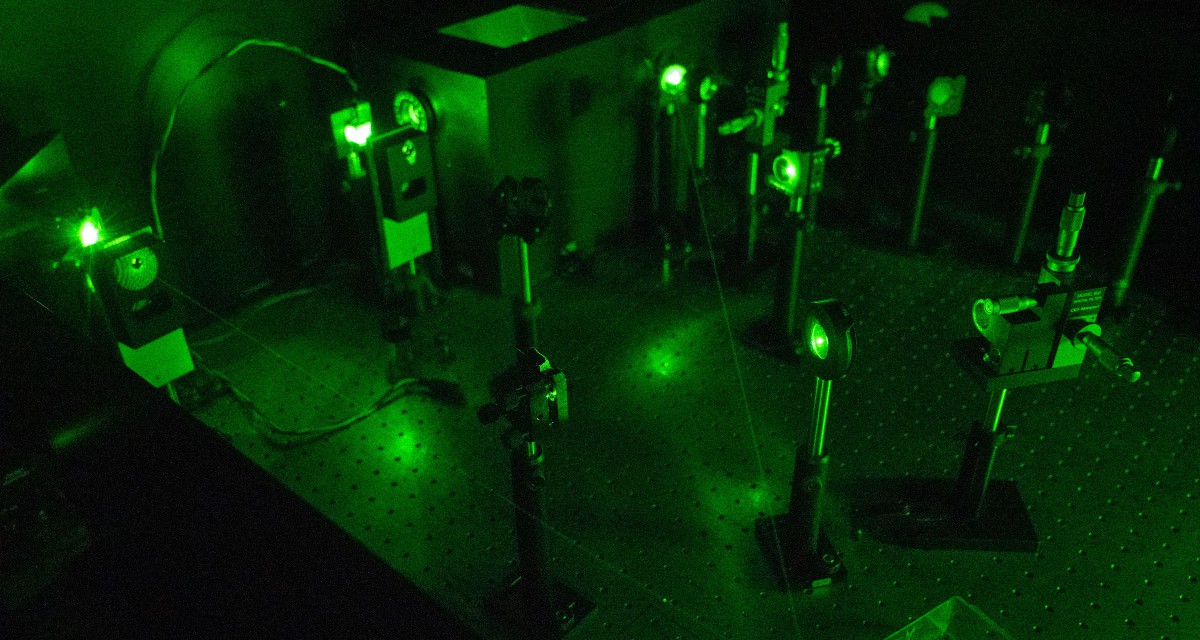

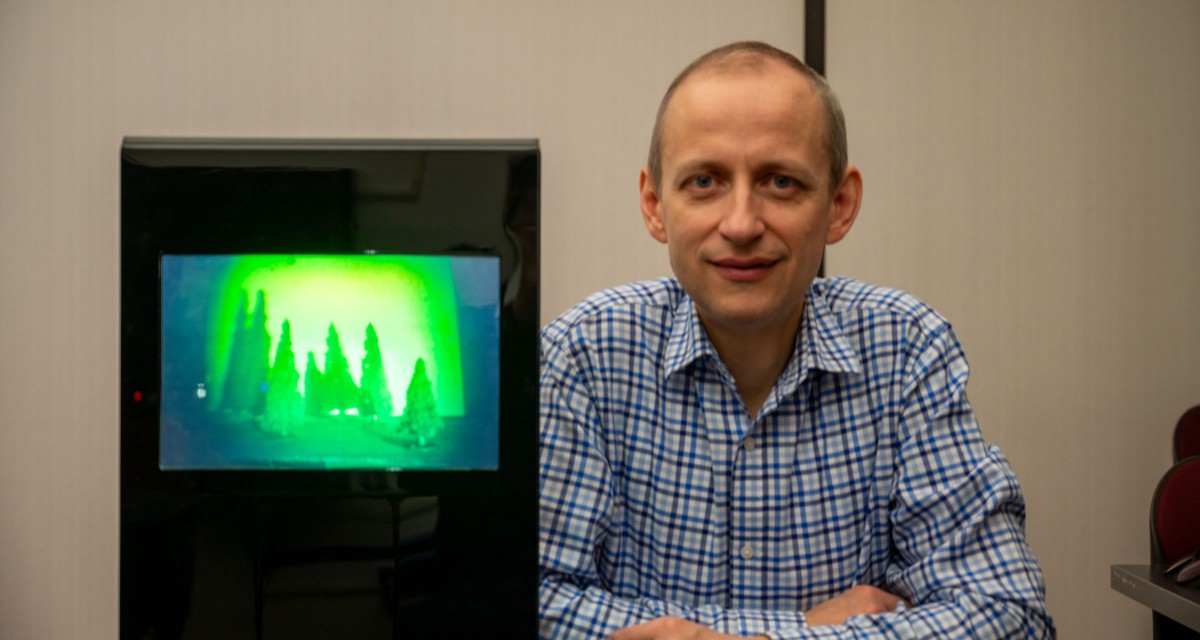

Professor Emanuel Istrate's course blends science and art, offering a one-of-a-kind learning experience at U of T. (Photos by Minh Truong)

By Dan Blackwell

Squirrelled away in a small physics lab on St. George campus, Victoria College Professor Emanuel Istrate is putting his PhD in photonics to work. Alongside a few undergrads, Istrate is adjusting small mirrors to precisely reflect a high-powered neon green laser on an optical table. The goal: to create holograms that are not merely optical illusions or colourful facsimiles of real-world objects, but also works of art.

Istrate has been teaching his class “Holography for 3D Visualization,” since 2008. It offers undergrads from all disciplines something no other course at U of T can: hands-on experience creating display holograms. It’s a distinctly Vic experience that seamlessly blends art and science into a unique learning opportunity.

“You could teach this science on a chalkboard or in a PowerPoint, but here we say, ‘let’s do this in person, let’s make holograms’,” says Istrate. “We’ve made holography into a reliable, teachable process where you can have a classroom of 30 students come in and at the end of the term, they each have created something special.”

Unlike holograms found on a sticker or on the back of a credit card, Istrate’s are three-dimensional images developed on film that can uncannily recreate depth, detail and movement without needing goggles or special eyewear. These images are so elaborate that they can be seen only when mounted in special frames designed to direct light onto a mirror at precisely the right angle.

While holograms have been around since the 1940s, it’s rare for undergraduates to have access to the equipment necessary to create them, much less make art with them, says Istrate.

“Holography, when it was first discovered, was the exclusive domain of scientists,” he says. “They would often take any everyday object to make a hologram because the subject of the image never mattered—it was the physics that mattered. Here, we do display holography for artistic purposes.”

Istrate’s 12-week course consists of both classroom lectures and laboratory sessions. In the classroom, students gain a thorough understanding of the science and history of holograms. Things get interesting in the lab where students pair up, pitch ideas and collaborate on creating two holograms.

“You learn about optical physics, and you have to learn and understand the mechanical steps involved in creating holograms,” says Istrate. “At the same time, you can’t just make a hologram of your cellphone because then you are going to fail the artistic component of the course.”

The first hologram students create involves a real-world object, something crafted or sculpted from clay or cardboard, or even a figurine or other small object. The second hologram is composed by students digitally using 3D graphics software.

While both types of holograms take about three hours of lab time to set up and develop on film, it’s an incredibly precise process.

“Holography is very sensitive to vibrations,” Istrate says. Even the slightest disturbance, like the reverberations from a nearby subway line, can throw the whole process off. “Anything that moves during your exposure vanishes.”

That’s why Istrate’s optical table is equipped with hydraulic legs to ensure stability, one of the many high-tech components needed to teach this course. Istrate estimates that the value of the optical, electronic and mechanical equipment in his lab exceeds $100,000.

While the equipment in Istrate’s lab is special, he says it’s the course’s approach to uniting diverse disciplines that makes the experience a worthwhile investment.

“We have participants who study computer science, but we also have students with a passion for poetry and various artistic expressions, along with a significant presence from the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design,” he says.

“We encourage students to work with peers from different academic backgrounds because it’s often this type of partnership that yields the greatest rewards.”

Emily Su, a third-year student majoring in statistics and minoring in computer science and digital humanities, says she was lucky to be paired with an English major.

“My partner, Elaiza Palaypay, minors in visual studies, and her background was more on the arts side,” says Su. “We were able to divide the work equally. I was able to learn a lot from her about art in general, and we worked and learned together about the physics portion of the program.”

Istrate says his course takes a different approach to interdisciplinary learning.

“Universities require students to take courses outside of their comfort zone or primary area of study, but we often don’t follow up with these learnings when the course is over,” he says. “This course proposes that students come and learn about both the humanities and sciences together in one setting.”

The holograms Su and her partner created reflect this ethos of integrating arts and science.

One hologram portrayed the tale of the Greek goddess Persephone, while the other was a 3D model of Jupiter that shows both its exterior and a secret civilization hidden within the planet’s interior depending on which side of the hologram you look at.

“We did a lot brainstorming and adding on to each other’s ideas,” says Su. “We didn’t intentionally set out to make one project more art-focused and the other to be more scientific, but that’s just how it came to be.”

Istrate emphasizes that this blending of arts and science (intentional or not) is about much more than expanding one’s horizons—these learnings have real-world applications.

“Working with people from different backgrounds and with different skillsets is very valuable as a life skill,” he says. “The world is not always based on disciplines. There are some jobs out there that require great specialization, but most jobs demand generalists.”

Istrate says the more students can change the way they think, the better they’ll be equipped to enter the workforce.

“Not many people will have to learn how to align optical lenses for their work,” he says. “It’s the skill of coming up with a project and managing it from end to end that is something you need to learn. It’s about problem-solving, working with others and finding unique solutions for complex issues.”

Su says the course offers the training necessary to pursue careers in a variety of industries.

“The hands-on experience is the most valuable thing for me. Coming out of the course you have made something that shows you not only know how to create art, but also that you understand the physics and development steps involved in the scientific process.”

Like the holograms crafted by his students, Istrate’s course is designed to shift perspectives, encouraging individuals to view things from a fresh angle.

“It’s really about keeping an open mind and learning that there are other ways of seeing things. A common criticism of the university is that there are silos of academia. At Vic, we’re trying to bridge the gaps between disciplines and this course is one the most extreme and unique examples of this.”

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of Vic Report.